Originally posted on 12th Jul 2018

Every half-eaten pretzel, abandoned newspaper, and sealed meal tray from another country becomes someone's problem the moment it touches U.S. soil. Airport waste management handles this through layered systems: terminal waste segregation where passengers toss coffee cups, airline cabin waste recovery where flight attendants bag untouched meals, USDA-regulated destruction of international food waste, and airport recycling programs pushing toward 90% landfill diversion. A hub processing 50 million travelers annually—generating roughly 1.0 to 1.5 pounds of waste per passenger—manages the refuse output of a mid-sized city. The industry is shifting from "dispose and forget" to "recover and reuse," treating waste streams as resources rather than endpoints.

Key Takeaways

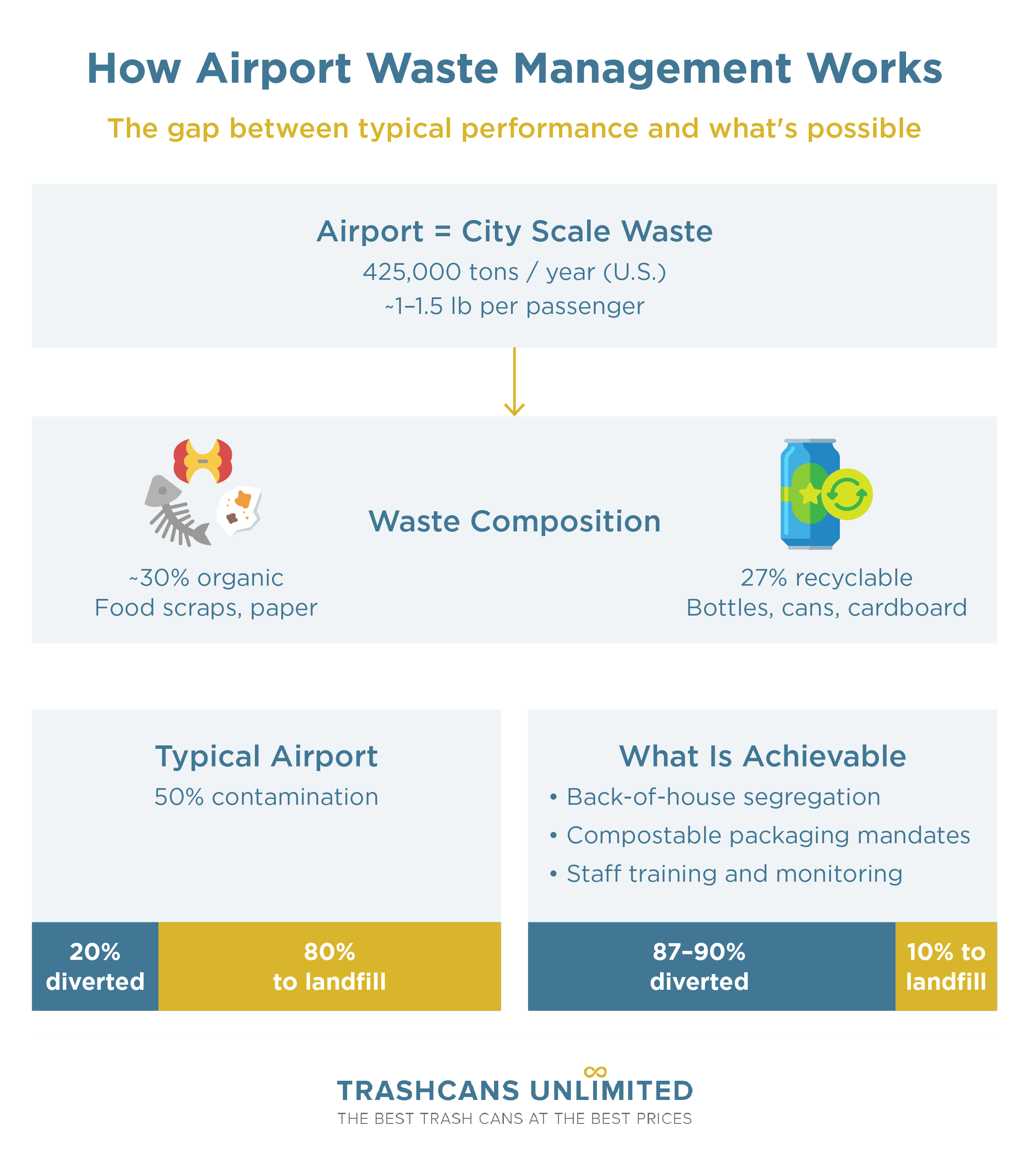

- Scale: U.S. airports generate approximately 425,000 tons of waste annually, with 1.28 pounds per passenger departure in terminals and 0.94 kg per passenger in cabin waste.

- Regulatory complexity: International waste falls under USDA APHIS regulations (7 CFR 330.400-403), requiring incineration or sterilization within 120 hours of arrival—no exceptions.

- Diversion is achievable: Leading airports like San Diego (87% diversion) and San Francisco (targeting 90% by 2030) prove high diversion rates are possible with systematic programs.

- Back-of-house wins: Denver's Zero Waste Valet achieved 71% diversion for participating concessions versus 21.4% facility-wide—a more than threefold improvement through dedicated support.

- Contamination is the enemy: Studies show up to 50% contamination in airport recycling streams, yet 60% of landfill-bound material is actually recyclable or compostable.

- Circular economy potential: Airline initiatives like Delta's paper cups (eliminating nearly 7 million pounds of single-use plastic annually) demonstrate upstream waste prevention works.

Understanding the Scale: How Much Waste Do Airports Generate?

The break room at your local airport probably has a poster about recycling. What it doesn't show is the 12,000 tons of waste Denver International processed last year—roughly the weight of the Eiffel Tower—or the 425,000 tons U.S. airports collectively generate annually. That's the municipal waste equivalent of a city of 500,000 people, compressed into terminals, jetways, and tarmacs.

Without grasping this magnitude, conversations about sustainability remain fantasy.

Waste Volume Statistics and Industry Benchmarks

The numbers vary by how you slice them. NRDC research documented 1.28 pounds of waste per passenger departure across terminal areas, retail tenants, and airline operations. IATA's 2023 Aviation Sustainability Forum analysis found airlines generated 0.94 kilograms (about 2.1 pounds) of cabin waste per passenger—totaling 3.6 million tonnes globally that year.

That cabin figure will double by 2040 at current growth rates. For sustainability directors, this isn't abstract environmentalism—it's a capital planning problem. Waste infrastructure designed for today's volumes won't survive 2040's passenger counts.

San Diego International diverted nearly 60,000 tons in 2019, achieving 87% diversion when including construction debris. That's not typical. NRDC research suggests the overall airline and airport industry recycling rate hovers below 20% without aggressive intervention.

Mapping Airport Waste Stakeholders: Who Generates What

Here's the uncomfortable truth: no single entity controls the waste stream. Four groups generate airport waste, and they rarely coordinate.

- Passengers create the visible chaos—food packaging, bottles, magazines tossed before security or at gates. This stream spikes unpredictably (try managing waste the Wednesday before Thanksgiving) and consists largely of food-contaminated plastics that complicate recycling.

- Airlines produce cabin waste—catering returns, amenity kits, newspapers, the single-use plastics mandated by food safety rules. An IATA-commissioned Heathrow study found 23.4% of cabin waste was untouched food. Another 17.3% was recyclable material that, due to commingling and international waste regulations, couldn't be recovered.

- Concessioners generate the most controllable stream: food prep scraps, cardboard boxes, beverage containers from back-of-house operations. Kitchen staff can be trained. Lease requirements can be enforced. Performance can be measured.

- Airport Operations handles terminal cleaning, landscaping, and construction. During major capital programs, construction debris can dwarf everything else.

Airlines lease space under agreements that may not mention waste. Concessioners operate under separate contracts. Passengers are anonymous and transient. This fragmentation explains why well-funded airports struggle past 20% diversion without comprehensive policy overhaul.

Unique Challenges of High-Traffic Terminal Environments

Airport waste management isn't restaurant waste management with longer hallways. The constraints are fundamentally different.

- Throughput volatility: A food court producing 500 pounds on Tuesday might produce 1,500 pounds before a holiday. Design for averages and you fail during peaks. Design for peaks and you waste resources 80% of the time. Fill-level sensors address this by enabling dynamic collection.

- 24/7 operations: No overnight shutdown for equipment maintenance or deep cleaning. Everything happens during live operations, often in passenger-visible areas.

- Security constraints: Post-security waste can't easily merge with pre-security streams. Collection routes navigate checkpoints. Hazmat screening intercepts items requiring special handling.

- International regulations: Airports with overseas traffic maintain completely separate waste streams with documented chain-of-custody (more on this below).

- Limited back-of-house space: Terminals built in the 1970s prioritized retail square footage over service infrastructure. Many airports lack room for multi-stream collection, compaction equipment, or temporary storage—forcing expensive transport to remote processing facilities.

These problems are solvable. But solutions borrowed from hotels or shopping malls fail in aviation environments.

Types of Airport Waste: From Terminal Trash to Regulated International Waste

Different waste streams require different handling, different infrastructure, and different regulatory compliance. Treating all waste identically guarantees poor outcomes across every category.

Terminal Solid Waste: Everyday Passenger and Retail Streams

This is the visible stream: food packaging, beverage containers, newspapers, retail bags. It's also the primary recycling opportunity.

Passenger waste is dominated by coffee cups with plastic linings (non-recyclable), clamshell containers, plastic utensils, napkins, and bottles. Sorting compliance varies wildly based on bin design, signage clarity, and whether travelers recognize the color-coding. What signals "recycling" in Portland may signal "trash" in Paris.

Retail and restaurant waste splits into front-of-house (customer-facing) and back-of-house (kitchen) streams. Back-of-house is cleaner—prep scraps, cardboard, packaging—and responds well to systematic programs. Front-of-house mixes customer mess with post-consumer residue, creating contamination.

Strategic bin placement dramatically affects outcomes. Research shows that bin design matters as much as signage—openings sized for specific materials (round holes for bottles, slots for paper) improve accuracy even when passengers don't read instructions. Lobby and airport trash cans with clear compartmentalization demonstrably reduce contamination.

International Waste: USDA APHIS Regulations and Quarantine Requirements

International waste is the most heavily regulated stream. Get it wrong, and your operating status is at risk.

USDA APHIS regulates "regulated garbage" under 7 CFR 330.400-403 and 9 CFR 94.5. The definition covers any waste from fruits, vegetables, meats, or animal materials aboard conveyances visiting ports outside the U.S. and Canada within two years—or traveling to/from Hawaii and U.S. territories within one year.

The scope is deliberately broad. Foreign agricultural pests—foot-and-mouth disease, African swine fever, plant pathogens—can enter through improperly handled food waste. One disease introduction could cost billions.

Disposal requirements are correspondingly stringent: incineration, sterilization (autoclaving), or approved grinding that renders material biologically inactive. As of January 3, 2022, APHIS extended maximum storage from 72 to 120 hours—a modest operational flexibility.

Compliance agreements (PPQ Form 519) formalize requirements for any entity handling international waste. The mandates include:

- Secure storage separated from domestic waste

- Leak-proof, covered receptacles (red containers resembling medical waste are prohibited)

- Enclosed, lockable transport vehicles

- Documented chain of custody from aircraft to final processing

- Three-year record retention for spill/disinfection/sanitation logs

- New compliance agreement handlers monitored quarterly by APHIS/CBP for the first year, then every six months thereafter

Recycling exemptions are narrow. Cans, glass, and plastic containers (not dairy) may be recycled if stored separately and uncontaminated. Clean cardboard and paper qualify under specific conditions. Critically, no sorting of APHIS regulated garbage is permitted outside the aircraft—severely limiting international cabin waste recycling.

International waste management is both compliance obligation and significant cost center. Specialized handling costs more than municipal processing. Airlines typically bear these costs, but infrastructure and oversight burden falls on airport operations.

Hazardous and Special Waste Management at Airports

Beyond international waste, airports generate several specialized streams.

- Aircraft maintenance waste—oils, hydraulic fluids, solvents, contaminated rags—falls under RCRA hazardous waste rules requiring manifested disposal through licensed transporters.

- De-icing fluids present seasonal challenges. Propylene and ethylene glycol agents have high biochemical oxygen demand and cause water quality impacts if released untreated. Denver International's closed-loop system captures approximately 70% of applied fluid and reprocesses it for reuse—environmental management and operational efficiency aligned.

- Electronic waste from abandoned passenger items and operational equipment contains valuable recoverable materials alongside hazardous components requiring specialized handling.

- Medical waste from first aid stations and in-flight incidents requires segregated collection through licensed contractors.

The operational principle: segregation. These materials must never contaminate general streams, recyclables, or create worker safety hazards.

Airport Recycling Programs and Waste Reduction Strategies

Understanding waste streams provides context. Implementing diversion programs is where airports actually reduce impact—and often costs.

Source Segregation: The Foundation of Effective Airport Waste Management

Source segregation—separating materials at the point of generation—is the single highest-impact intervention. Materials sorted correctly at source process efficiently. Materials contaminated through commingling often can't be recovered at any cost.

Denver International's experience illustrates the gap between potential and practice. Overall diversion hovered around 20%, but a 2023 waste composition study revealed about 60% of the waste at the airport is divertible—a little over 30% from organic materials that could be composted, and 27% recyclable. Meanwhile, 50% contamination in the recycling stream meant half of collected recyclables were ultimately landfilled anyway.

- Bin placement affects behavior more than you'd expect. High-traffic locations generate the most waste and benefit most from multi-stream collection. But bins must sit where passengers naturally pause—not in high-speed pedestrian flows where people toss without thinking.

- Visual design must work across languages and varying recycling familiarity. Images outperform text. Standardized colors help, but international passengers may read them differently.

- Back-of-house segregation offers more control. Kitchen staff can be trained. Organic streams can be collected clean. Performance can be monitored through lease requirements. Denver's Zero Waste Valet achieved 71% diversion for participating concessions versus 21.4% facility-wide—more than a three-fold improvement through dedicated support.

Commercial-grade trash cans for terminal environments must withstand constant use, facilitate proper sorting, and accommodate efficient custodial servicing. Equipment selection directly affects diversion outcomes.

What Airports Actually Recycle: Materials, Rates, and Challenges

Grounding sustainability discussions in operational reality means acknowledging what airports can actually recover.

- Primary recyclable streams include aluminum beverage cans (high-value with established markets), PET bottles (recyclable when empty and uncontaminated), cardboard and paper (major stream from shipping and publications), and glass (recyclable but often deprioritized due to weight and logistics).

- Contamination remains the central challenge. Food-soiled paper, liquids in bins, incorrect sorting—all reduce value and recyclability. IATA's Heathrow study found that while 17.3% of cabin waste was technically recyclable, regulations and contamination meant most couldn't actually be recovered.

- Benchmarks vary dramatically. San Francisco targets 90% diversion by 2030 through aggressive airport sustainability programs including mandatory compostable foodware and elimination of single-use plastics. San Diego achieved 87% (including construction debris) with a 90% goal by 2035. Denver's 21% reflects what happens without comprehensive intervention.

- Single-stream versus source-separated recycling presents a strategic choice. Single-stream simplifies passenger decisions but increases contamination. Source-separated produces cleaner streams but demands more bins, space, and user decisions. Most airports go hybrid—single-stream in passenger areas, source-separated back-of-house.

Airport Composting and Organic Waste Diversion

Organic waste—food scraps, food-soiled paper, landscape trimmings—represents a significant portion of the typical airport waste stream. Diverting it reduces methane emissions and produces valuable compost.

- Pre-consumer food waste from kitchens is the cleanest stream. Prep scraps, expired ingredients, and trim waste can be collected with minimal contamination. Commercial kitchens typically generate more organic waste from preparation than from customer plates.

- Post-consumer food waste is harder due to packaging contamination. Compostable packaging helps: when utensils, containers, and napkins all compost, entire plate-clearing streams can follow. The trade-off is operational coordination and often higher procurement costs.

California SB 1383 mandates organic waste collection and edible food donation at large venues including airports. San Francisco's Replate partnership for food recovery exemplifies compliance while supporting community organizations.

Scale determines processing approach. Small airports lack volumes for on-site composting; major hubs may find on-site handling improves logistics. Denver's airport composting program, though COVID-interrupted, demonstrated that back-of-house organic collection significantly boosts diversion when properly resourced.

Circular Economy Strategies for Aviation Sustainability

Recycling addresses waste after creation. Circular economy approaches at airports eliminate it at the source through material selection, product design, and closed-loop systems.

- Concessioner partnerships represent the highest-leverage intervention. Airports mandating compostable or recyclable packaging eliminate entire contamination categories. San Francisco's Zero Waste Concessions Program requires elimination of single-use plastic foodware entirely—shifting from "managing plastic waste" to "not generating it."

- Reusable container programs eliminate single-use packaging entirely. App-based systems let passengers receive food in reusable containers and return them to collection points. Implementation requires washing infrastructure, loss replacement systems, and sustained passenger participation—but eliminates packaging waste for participating transactions.

- Airline initiatives attack cabin waste upstream. Delta has tested paper cups to eliminate nearly 7 million pounds of single-use plastic annually. Iberia's Zero Cabin Waste project targets 200,000 kg of plastic reduction. SWISS lets passengers pre-order meals, reducing untouched food waste through more tailored catering uplifts.

The circular framing transforms waste management from cost center to strategic function—affecting vendor relationships, procurement decisions, infrastructure planning, and passenger experience.

Waste-to-Energy Systems at Airports

Waste-to-energy converts non-recyclable material into electricity or heat through controlled combustion. For airports, WTE is especially relevant for international waste requiring incineration anyway.

- Co-location advantages emerge when airports can direct streams to nearby WTE facilities. Mandatory incineration of international waste becomes productive—generating energy while meeting APHIS requirements.

- Trade-offs merit honesty. WTE produces air emissions requiring pollution controls, and critics argue energy recovery reduces upstream reduction incentives. But for material that can't be recycled or composted—contaminated streams, international waste, certain plastics—WTE beats landfilling.

San Francisco International has explored co-digestion of organic waste with wastewater sludge at its on-site treatment plant, producing biogas as renewable energy. The integrated approach addresses multiple streams while generating local power.

Challenges and Innovations in Airport Waste Systems

Even committed airports face persistent obstacles. Honest acknowledgment enables realistic planning.

Operational and Cost Barriers to Better Waste Management

- Space constraints may be the most intractable challenge. Terminals from the 1960s-1990s allocated minimal back-of-house space, assuming waste would simply disappear. Retrofitting multi-stream collection into existing buildings means stealing revenue-generating space or accepting suboptimal logistics.

- Cost pressures create real tension. Comprehensive programs require dedicated staffing for education and monitoring, equipment for multi-stream collection, and often higher processing costs for composting. These expenses are immediate and ongoing; benefits—reduced tipping fees, recyclable commodity revenue, avoided emissions—take years to materialize and resist quantification in budget documents.

- Stakeholder coordination complexity can't be overstated. Airlines follow federal regulations and global corporate policies. Concessioners are national brands with franchise standards. Ground handlers, cleaning contractors, and waste haulers add organizational boundaries. Achieving consistency across this landscape requires sustained engagement, contractual requirements, and ongoing monitoring.

- Passenger behavior remains stubbornly resistant. Despite decades of recycling education, contamination in high-traffic airport environments can reach 50%. Passengers are rushing, distracted, unfamiliar with local rules. Some contamination is inevitable; the question is designing systems that minimize its impact.

Smart Waste Technology and AI-Powered Sorting Systems

Technology offers genuine solutions, though vendor claims often exceed real-world performance.

- Fill-level sensors represent mature, proven technology. Ultrasonic or infrared sensors monitor capacity and transmit data to management systems, enabling route optimization and overflow prevention. Multiple airports report significant efficiency gains—reduced trips, better labor allocation, cleaner terminals.

- AI-powered sorting guidance is emerging at passenger touchpoints. Seattle-Tacoma deployed "Oscar," an Intuitive AI system analyzing items placed before cameras and directing passengers to appropriate bins. Early results suggest improved accuracy and valuable composition data. Importantly, cameras capture only waste items, not identifying passenger information.

- Robotic sorting for material recovery facilities represents the most ambitious application. Computer vision systems can identify and sort recyclables at rates of 80 items per minute with accuracy up to 99%. These systems are transforming large-scale recycling, though airport-specific deployment remains limited.

- Solar-powered compacting bins increase capacity by compressing waste in place, reducing collection frequency. For airports, reduced servicing translates directly to labor savings and less passenger-area disruption.

The appropriate stance is selective adoption. Fill-level monitoring is proven and widely applicable. AI guidance shows promise and warrants piloting. Robotic sorting transforms MRFs but isn't yet relevant for most airports. Speculative technologies deserve pilots before scale.

Stakeholder Alignment: Airlines, Concessioners, and Passenger Engagement

Ultimately, waste management is a coordination problem. Technology and infrastructure matter, but outcomes require aligned incentives across stakeholder groups.

- Airline engagement must address cabin waste specifically. Airlines control meal planning, packaging selection, and service protocols—decisions predetermining waste composition. Forward-thinking airports convene sustainability working groups, share audit data, and explore joint initiatives. Airlines are motivated by environmental commitments and cost reduction—less waste means lower catering and disposal expenses.

- Concessioner contracts provide the most direct lever. Lease agreements can require recycling and composting participation, mandate compostable packaging, establish diversion targets with consequences, and require staff training. Requirements must balance against economics—overly burdensome mandates may increase costs, reduce competition, or simply be ignored.

- Passenger education works best when it asks less of passengers. Effective interventions simplify decisions rather than demanding knowledge: bins with openings shaped for specific items, images instead of text, liquid disposal stations before security. Expecting passengers to become sorting experts is unrealistic.

- Industry benchmarking through ACI and ACRP provides comparative data and best practice documentation, helping sustainability directors build evidence-based cases and learn from peers.

The Future of Airport Waste Management: Zero-Waste Goals and Beyond

The trajectory is clear, even if timelines remain uncertain: regulations tightening, expectations rising, operational cases strengthening.

Zero-Waste Airport Commitments and Progress

"Zero waste" in airport context means diverting 90%+ from landfill through recycling, composting, and waste-to-energy—not literal elimination.

- San Francisco International aims to become the world's first zero-waste airport, targeting 90% diversion by 2030. The SFO Zero Waste Plan codifies mandatory compostable foodware, single-use plastic elimination, and systematic stakeholder engagement. SFO has achieved airport-wide LEED Platinum certification—the first in the world.

- San Diego International adopted a Zero Waste Plan in 2019 targeting 90% by 2035, with interim 10% per-passenger reduction goals. The 87% diversion achieved in 2019 (including construction debris) demonstrates zero-waste goals are achievable.

- Denver International has committed to becoming "the greenest airport in the world." The Zero Waste Valet pilot—71% diversion for participating concessions versus 21.4% facility-wide—demonstrates targeted interventions' potential. Airport leadership plans expansion across all concourses.

Accountability frameworks matter as much as commitments. Leading airports pursue third-party certification through TRUE Zero Waste, providing independent verification and enabling meaningful facility comparison.

Evolving Regulations and Policy Trends

Regulatory requirements are moving one direction: mandatory diversion, organic collection, extended producer responsibility.

- State and local mandates increasingly require large venues to implement composting and recycling. California's SB 1383 mandates organic collection and edible food recovery. Similar requirements are emerging elsewhere. Airports delaying implementation may face compliance scrambles.

- Carbon accounting is beginning to incorporate waste emissions. Scope 3 inventories increasingly include disposal—meaning waste performance affects reported footprints. For airports with climate commitments, diversion becomes carbon reduction strategy.

- Harmonization efforts through ICAO, ACI, and IATA continue. While waste lacks sustainable aviation fuel's profile, industry-wide measurement and reporting standards would enable meaningful benchmarking.

The Circular Airport Vision: From Disposal to Resource Recovery

The fully circular airport remains aspirational, but the framework guides current decisions.

- Waste streams become inputs. Food scraps return to agriculture as compost. Construction materials are specified for future recyclability. Packaging is designed for recovery. The goal: design operations that generate less waste requiring management.

- Infrastructure enables circularity. Terminal designs accommodate multi-stream collection and on-site processing. Contracts specify material requirements, not just disposal responsibilities. Procurement considers full lifecycle impacts.

- Airports model sustainability for their regions. Millions of passengers pass through annually. The recycling bins, water stations, and sustainability messaging they encounter shape expectations they carry elsewhere.

This vision connects waste management to broader aviation sustainability efforts. Airlines invest billions in sustainable fuel and fleet modernization. Airports deploy renewables and electrify ground equipment. Waste management is one component—not highest-impact, perhaps, but visible to passengers and achievable with current technology.

Transforming Airport Waste from Burden to Opportunity

Airport waste management is undergoing fundamental reframing. What was once compliance burden—meet regulations, haul waste away, minimize costs—is becoming strategic function touching procurement, stakeholder relationships, infrastructure, and passenger experience.

The scale is significant: hundreds of thousands of tons annually, volumes projected to double by 2040. The complexity is real: fragmented stakeholders, regulated international streams, security constraints, infrastructure limitations absent elsewhere.

Yet opportunity matches scale. Airports investing in comprehensive programs—San Francisco, San Diego, increasingly Denver—demonstrate 80-90% diversion with systematic approaches. The tools exist: segregation protocols, smart technology, stakeholder frameworks, circular economy strategies.

Three strategies that tend to offer highest leverage:

- Invest in back-of-house diversion first. Concessioner kitchen waste is cleaner, more consistent, more controllable than passenger areas. Denver's Zero Waste Valet achieved more than threefold higher diversion through dedicated back-of-house support.

- Address contamination at source. Liquid disposal stations, bin designs preventing incorrect sorting, policies requiring compostable packaging—all reduce contamination more effectively than downstream sorting.

- Build measurement into operations. Waste audits, fill-level monitoring, and diversion tracking enable evidence-based management and demonstrate ROI for continued investment.

The path from 20% to 90% diversion is neither quick nor cheap, but it's well-documented by peer airports. For facilities willing to invest systematically, airport waste management shifts from cost center to sustainability demonstration.

For airports and aviation facilities seeking commercial-grade waste receptacles designed for high-traffic environments, Trashcans Unlimited offers solutions engineered for durability and compliance. Contact us to discuss your facility's waste infrastructure needs, or explore our lobby and airport trash cans and commercial-grade options.